by Todd Bensman

President Joe Biden’s Department of Homeland Security (DHS) refuses to publicly identify the dozens of U.S. international airports for which it has approved direct flights from abroad for certain inadmissible aliens. At least 386,000 migrants through February have been allowed to fly to interior U.S. airports as part of a legally dubious admissions program the administration launched in October 2022. The rationale for the program is to “reduce the number of individuals crossing unlawfully” over the southern border — by flying them over it directly into the interior and then releasing them on parole.

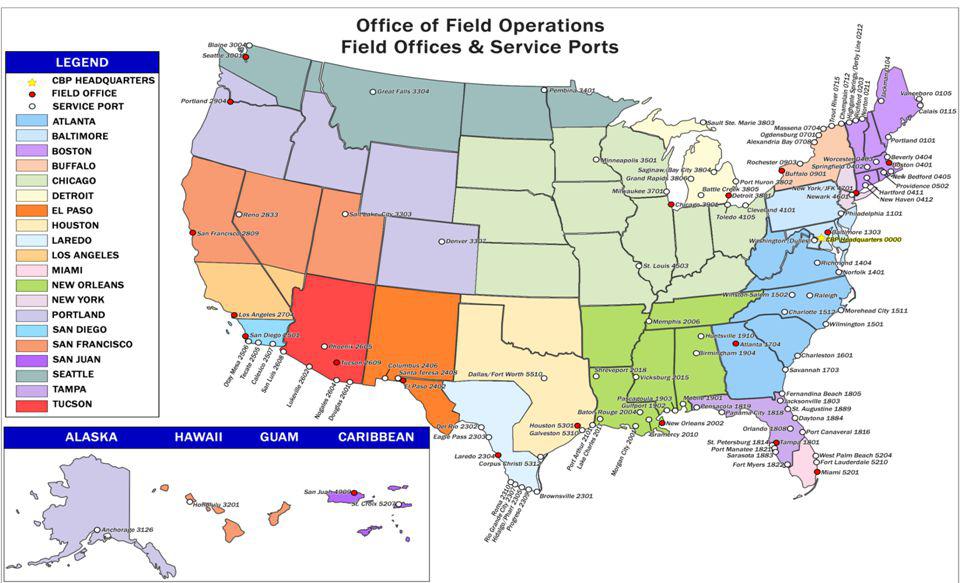

But a Center for Immigration Studies (CIS) analysis of available public information on U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) website, filtered to see Office of Field Operations (OFO) airport customs officer encounters with the nationalities chosen to receive this benefit, points out the airports that might account for most of the landings from abroad, if not necessarily the final destinations.

This early evidence suggests that a great many of these inadmissible alien passengers, probably a majority, initially land at international airports in Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis’s Florida. In fact, Florida turns out to be the top landing and U.S. customs processing zone for this direct-flights parole-and-release program, tallying at nearly 326,000 of the initial arrivals from inception through February.

Lesser numbers also are landing in the regions of Houston, New York, both northern and southern California, and the Washington, D.C., area, the data analysis reveals. But the data for Florida shows it to be heaviest for initial landings and migrant releases.

Public knowledge of where these flights deliver migrants should matter to local, state, and national leaders in cities struggling with migrant influxes, who could use the information to financially plan for their care, or petition the federal government to stop the flights. The information may also hold implications for litigation by Texas, Florida, and other states that have sued to stop the parole programs on grounds that the administration’s illegal abuse of the narrow statutory parole authority has directly harmed them.

Whether those hundreds of thousands stay in those areas or fly on after their initial landing and release is not shown in this data. Many of the landing Cubans, Venezuelans, and Haitians will obviously choose to stay in Florida, where expatriate communities are already large. But some percentage of the newly “legalized” aspiring border crossers who land there and in Texas, New York, and California likely transfer to domestic flights to their final destinations across the nation.

DHS would have that information. But this data analysis provides at least some contours of how the secretive program — sometimes referred to in government documents as the “CHNV program” or the “Advanced Travel Authorization” program — has been working.

Begun in October 2022 for Venezuelans and expanded in January 2023 to Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Colombians, the program approves flight travel authorizations for aspiring illegal border-crossers still in other countries to instead arrange commercial airline passage for themselves over the southern border and then receive temporary but easily renewable “humanitarian parole” from CBP officers at the airport. One incentive to dissuade beneficiaries from illegal border crossings is that the parole program comes with eligibility for renewable work permits.

Also during 2023, the direct-flights parole program declared that Guatemalans, El Salvadorans, Hondurans, and Ecuadorians also would be eligible, for a total of nine nationalities. The Central Americans and Ecuadorians show up in comparatively small numbers for now, having been added in the latter months of 2023, but could increase over time.

Filtering public CBP website data by those nine nationalities and including only non-land-border OFO Field Offices shows that in FY 2023 through February 2024, some 306,505 mostly Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Venezuelan beneficiaries flew into the Miami Field Office jurisdiction, which covers the bottom third of Florida.

The Tampa Field Office, which covers the rest of Florida, processed another 19,490 fliers during the same time span, beyond those processed through Miami OFO field office, for a total of 325,995 Florida presumed humanitarian parole grants by U.S. customs in international airports. Among those 325,995 were 3,821 Guatemalans, Salvadorans, Hondurans, Colombians, and Ecuadorians.

A substantial majority of those showing up in Florida airports, and the other regions, are single adults, but many also arrive in family units.

Other Initial Landing Zones

Meanwhile, another arrival destination turns out to be in Republican Gov. Greg Abbott’s Texas, at about an average rate of 1,500 per month. In total, some 21,964 arrived by air for CBP customs processing in the Houston Field Office (which also includes Oklahoma) from FY 2023 through February 2024. That field office covers the George Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston, one of the nation’s busiest for travel to and from Latin America.

Of those nearly 22,000 who flew into the OFO’s Houston Field Office, about 6,600 were Venezuelans, 6,300 were Nicaraguans, 5,400 were Cubans, and 500 were Haitians. About 3,100 were Colombians, Ecuadorians, Salvadorans, Guatemalans, or Hondurans.

Also revealed in the data analysis were receiving international airports serving cities whose elected leaders are complaining of crushing unfunded budget burdens from the arrival of hundreds of thousands of immigrants in recent years, not all of them by air, obviously. But some of them certainly by air as part of this direct-flight parole program.

The New York Field Office, which would cover JFK and LaGuardia airports, for instance, logged 33,408 OFO encounters with inadmissible aliens from the chosen nationalities for FY 2023 through February 2024.

Some immigrants also are flying into other areas where local leaders are struggling with an immigrant onslaught of resettlement — and loudly petitioning the federal government for relief.

These include for FY 2023 through February 2024, OFO field offices in: Los Angeles (8,382), San Francisco (4,578), Atlanta (4,515), Boston (4,879), Baltimore (3,784), and Chicago (1,556).

As will be explained below, these relatively small numbers are likely much higher than this data reflects because some migrant passengers arriving in major international airports as part of this parole program probably transfer to domestic flights to finish their travels to interior U.S. cities hours of additional flight time away.

Those domestic onward transfer flights would not be reflected in this OFO encounters data. The data also does not show any breakdown for flight arrivals in border states where OFO also staffs land ports of entry. An example would be the Tucson Field Office, which logged a massive increase in the nine nationalities — from 460 in 2022 to 10,550 in FY 2023 and 11,261 just so far in FY 2024 — with no breakout of direct-flight arrivals versus those processed in at land ports as part of the corresponding CBP One parole program.

Neither Republican governors in Florida or Texas, nor Democratic Party city leaders angry about the migrants showing up with hands out, have mentioned the humanitarian parole flights program as a contributor to any of their local mass migration-related problems. The silence is likely because, since its initial quite public announcement, the program drew little media follow-up or clearly delineated government reporting on how many are flying in, where, and became “obscure”, as the Wall Street Journal recently described it, until the Center for Immigration Studies published a recent report about why DHS refuses to disclose more — a report that Elon Musk and Donald Trump amplified.

Among those largely silent about the flights program that probably brought more than 33,000 immigrants to his city is New York City’s Mayor Eric Adams, who has struggled politically and financially to support an estimated 150,000 who have shown up since 2022. Mayor Adams has repeatedly and bitterly blamed these arrivals entirely, and with litigation, on Texas Gov. Abbott’s voluntary free busing program offered to migrants released on orders of the Biden administration after illegally crossing the border with Mexico.

No politicians in New York or Massachusetts have raised objections in the face of news reports that a Haitian who flew on one of the parole flights from Haiti to New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport allegedly went on to rape a minor migrant girl in a Massachusetts shelter.

Unlike with illegal border-crossers, the federal government can more quickly and easily increase or reduce the flights program on demand because it pre-approves each flight authorization. The Biden administration can modify this program at will, which means New York could have subtracted at least those 33,000 from the estimated 150,000 who have come to the region and reduced the burden of helping required financial sponsors provide government health care, education, public welfare assistance, and other material needs.

Very probably, though, the number who arrived from their foreign travels as part of this program exceeds those 33,000 who went through OFO processing in New York and also the smaller numbers that arrived on direct international flights in Boston, Chicago, and other airports farther north than Gateway Florida.

Re-Distribution by Domestic Air?

The data reflecting smaller numbers in some of these struggling northern cities, such as those in OFO’s Chicago Field Office, belies the potential that many using the humanitarian flight entry program are showing up on domestic flights to which they transferred after landing in Florida and Texas, rather than aboard international ones. If true, that would mean far more than reflected in this data are showing up after their long foreign travels in places like struggling Denver, Chicago, and Boston.

For one thing, the large expatriate populations of Cubans, Haitians, and Venezuelans who already live in Florida naturally will draw relatives and former neighbors fly into the Sunshine State to stay.

But others who land there and don’t want to stay would continue to northern cities aboard domestic flights. Taking second domestic transfer flights would be attributable to route scarcity from Latin America to U.S. airports with customs and officials stationed in them and to sheer distance; some northern cities are situated too far for nonstop international flights leaving especially distant South American airports.

This would explain why regional OFO offices in places like Oregon, Washington, Montana, and Michigan show no appreciable change in OFO encounters or why Chicago and Boston don’t show more.

The Biden DHS, however, almost assuredly possesses this domestic flight transfer data because applicants for the direct-flight parole program would have to declare destination city addresses where they could be reached.

Data Confirms Tight Correlation to Biden Flights Program

CIS derived these limited findings about some of the airports by filtering publicly available data on CBP’s “Nationwide Encounters” website, which allows examination of OFO customs agent processing, by nationality, in the 21 OFO field offices. Field offices that would include encounters at official land ports with Mexico were excluded, such as El Paso and Laredo, although airports in these field offices might also have received international flights.

Each OFO field office or sector may cover multiple states, cities, and airports, so receiving cities are informed guestimates based on airports in those jurisdictions where OFO customs officers are deployed. The filtered results reveal OFO customs officer processing activities of those nationalities in non-border jurisdictions that could mostly have occurred inside international airports.

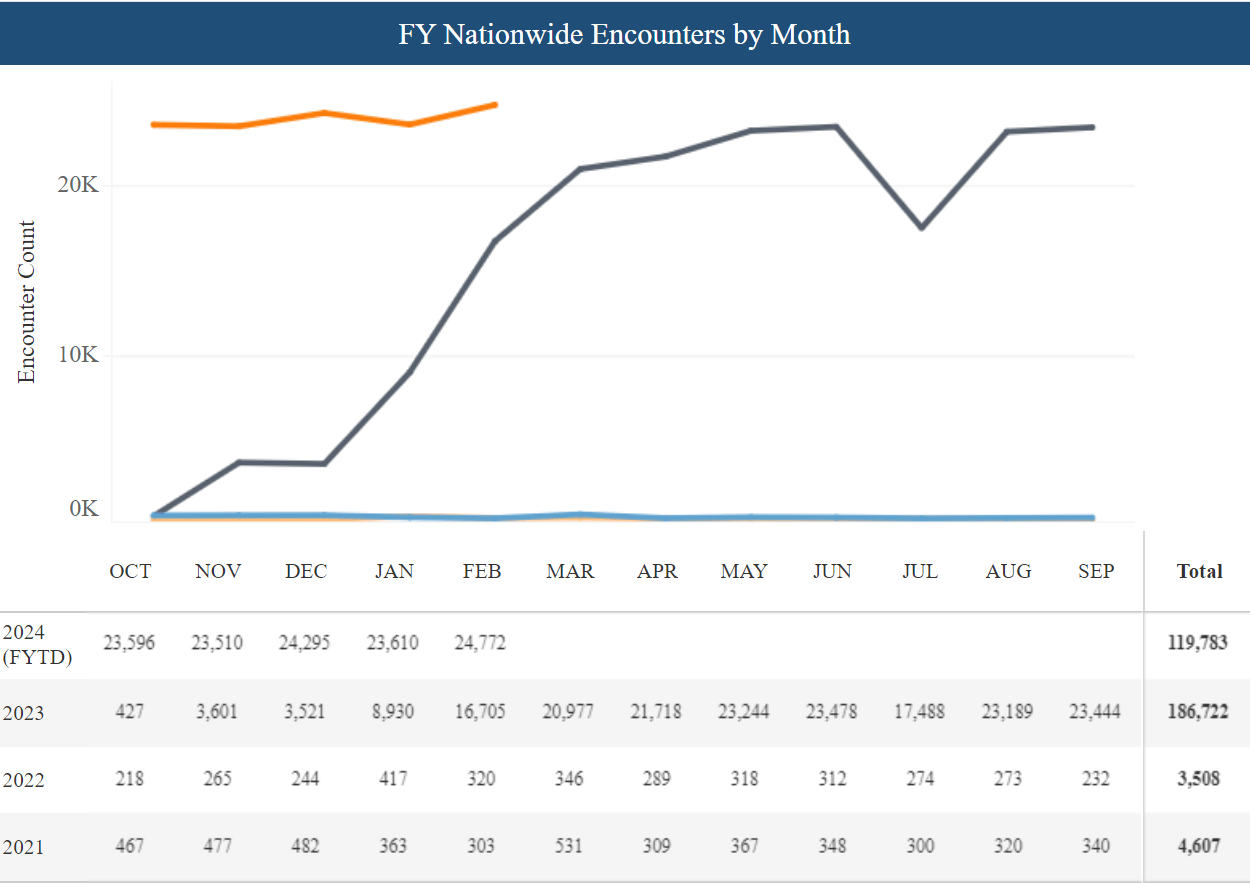

The data proves credible because increases in numbers the government previously released to the Center tightly correlate to government’s implementations of the CHNV parole program (October 2022 for Venezuelans; January 2023 for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans).

In fact, the numerical spikes show up in stark relief, the Miami Field Office a case in point. Prior to program implementation in 2023, the field office logged 4,607 customs officer encounters of the nine nationalities in FY 2021 and 3,508 in FY 2022.

But from that 3,508 in fiscal 2022, the office logged a hair-raising spike to 186,722 in FY 2023 for the nine nationalities, most of them Cubans, Haitians, Venezuelans, and Nicaraguans.

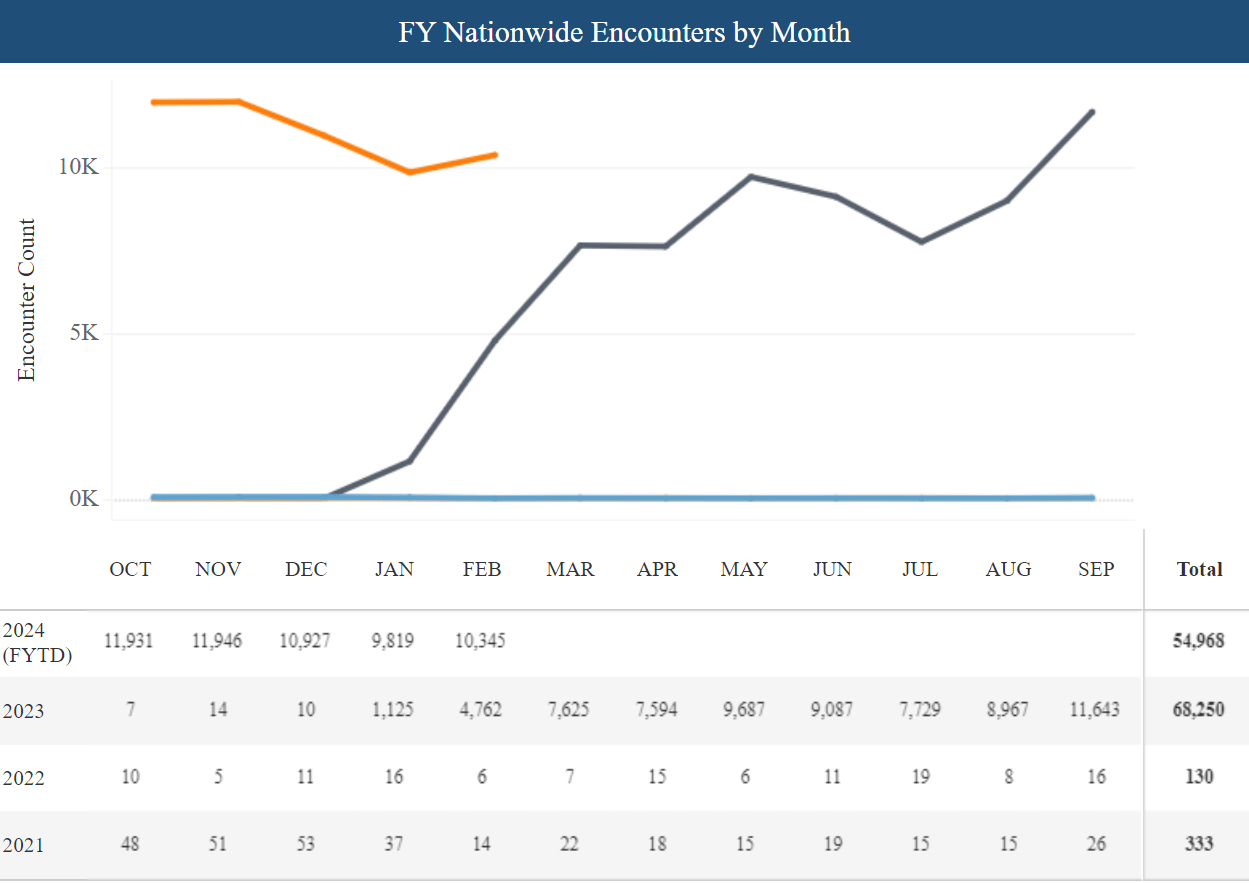

Take the number of Haitians, for instance. Their numbers ballooned from a mere 130 in FY 2022 to 68,250 in FY 2023, starting with the program’s January 2023 inception.

Likewise, the next most numerous nationality being processed through the Miami field office was Venezuelans. Their numbers exploded from 413 in 2022 to 47,200 in FY 2023. That spike showed up in November 2022, the first month after DHS announced the flights for them. Again, most of the incoming Venezuelans were single adults with family groups a distant second. They’ve been arriving in Florida at the rate of 3,000 to 5,000 per month.

In all of these regions where large numbers of the nine nationalities began showing up at U.S. customs in international airports, most flying in were single adults. Smaller numbers were family group members.

The Public Interest

But even this limited information does not tell the full story. CIS began seeking airport locations at home, plus foreign departure airport locations, early last year in a FOIA request.

The administration has declined, citing law enforcement exceptions. CIS has sued on grounds that the government violated the Freedom of Information Act. The information would be a matter of strong public interest to city leaderships, lawmakers, and voting publics to press for better planning of budgets and resources for those who might show up this way, or perhaps to demand redress from it — or demand that federal officials reduce or cease entirely the flight authorizations.

As for the foreign departure airports, transparency would provide visibility into who the government is actually approving for these flights, enabling reporters and advocates to interview participants abroad about their circumstances and the government’s application processes before the beneficiaries are lost amid general air traffic. (The direct-flight parole program is limited to the nine nationalities mentioned, but they may fly to the U.S. from anywhere.)

Administration lawyers refuse to identify those U.S. airports or the foreign departure airports on 7(E) law enforcement protection grounds that the flights program has so strained security staffing that is has created security vulnerabilities that “bad actors” could exploit if they knew where to go.

“There is the possibility that folks that have nefarious reasons — intentions to smuggle drugs, for instance, might try to go to those airports in which a lot of these foreign nationals are arriving under these processes,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Dedra Seibel Curteman told a Washington federal judge during a recent hearing on the matter.

CIS disputes that contention.

“It seems illogical and impractical that CBP would implement a program that admittedly caused staffing vulnerabilities at ports of entry,” said Colin Farnsworth, the Center’s chief FOIA counsel. “And instead of fixing those vulnerabilities to prevent exploitation by bad actors, CBP embraced those vulnerabilities to justify withholding information from the American public.”

– – –

Todd Bensman is the Center’s Texas-based Senior National Security Fellow. He is the author of “Overrun: How Joe Biden Unleashed the Greatest Border Crisis in U.S. History” and “America’s Covert Border War: The Untold Story of the Nation’s Battle to Prevent Jihadist Infiltration“. The Center for Immigration Studies is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit research organization founded in 1985. It is the nation’s only think tank devoted exclusively to research and policy analysis of the economic, social, demographic, fiscal, and other impacts of immigration on the United States.